| In what was a slight departure, they offered two shows per night, with 7 pm and 9 pm curtains. In addition, with a separate 7 pm show on Friday May 2nd, and a 9 pm show on Saturday May 3rd, Denise Fujiwara (the Artistic Director) performed her signature Noh piece, "Sumida River", for the last time in Toronto. I attended the 7 pm and 9 pm shows on May 1st.

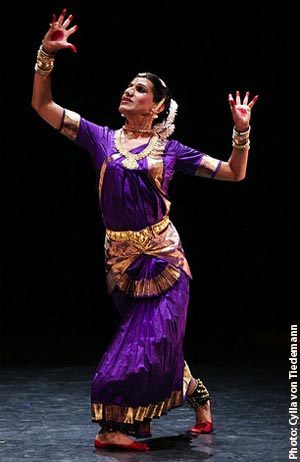

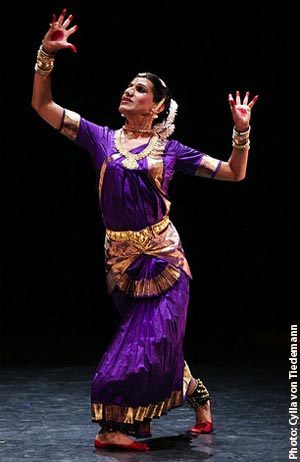

The 7 pm show opened with Hari Krishnan's 2006 Dora Mavor Moore award-winning piece, "Uma", where Sudarshan Belsare danced with authority to a powerful and animating voice-and-violin drone. Performed in the rich tradition of stri-vishnam (female impersonation in South India), the shifting geometry of Belsare's arms and legs and his mobile expressive eyes were fully 'in your face', but in an entirely good way. His vivid depiction of woman as lover, Goddess, wife, and virgin, had a sure magnetic pull. I can see the purple and gold satin dress, the gold jewellery, the aquiline profile, and the red-painted palms and soles of the feet. Belsare's solo was one of singular temple dance drama, sensuality, and humour.

Peter Chin's "Mind's Hammer" was an example of a closed system; a polar opposite of the preceding and expansive "Uma". A very 'actorly' dance and movement artist, Chin's wide range of facial and body gestures was, moment-by-moment, responsive, committed, and continuous. Chin also composed the music. Sometimes he'd motivate himself with a dissonant note, or he'd dance into a huge and flickering global environment created by the stepping marimba tones and the soft metallic clangs of the live gamelan orchestra. In the Programme booklet, Chin also exhorted us to "Resist Ruin" — and resist he does, right through to the dance's fourth and final section, "The Living House". Here, man has no desire to control his physical and spiritual environment. His great desire is to be alive, alert, and able to respond to the environment's ever-changing winds. Clearly, this piece was designed for the audience to look at. It wasn't asking for the usual empathy.

In stark contrast, bright costumes and a medium slow theatricality are what first distinguished Soojung Kwon's "The Choonengmu Project". Dressed in bright yellow, red, and blue, two women danced what seemed like separate dances on the same stage. Soojung Kwon danced a lead role. Her robed and head-dressed body rose and fell in a dynamic vertical line, as she essentially danced, statue-like, in one spot, and occasionally raised both arms in supplication. From out of the shadows of stage right, Johee Son, dressed in a traditional full-skirted dress, entered with smooth circular spinning movements. At times, it looked like Son was shadowing Kwon, but in fact she was offering a less formal and freer modern dance. At the same time, the very present live music was a Korean version of a two drums, one violin, one koto, and one percussionist sound. However, because I couldn't see nor feel much connection between the two contrasting dancers before me, my attention started to drift. But in the end, I came to feel that while Kwon's piece might have been conceptually modest, she did produce a desired-for dance deconstruction.

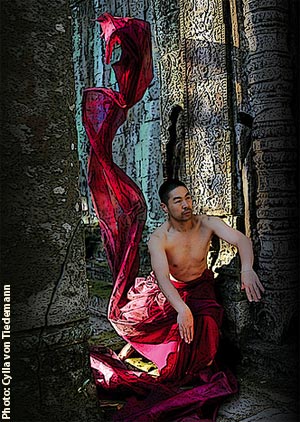

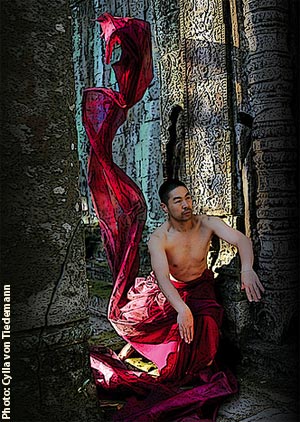

But in Wen Wei Wang's solo dance, "One Man's", there was absolute clarity of movement. It proved to be one man's self-expression through the medium of dance. Wang spoke to the audience from a kneeling position. He talked about being a little boy in China and his first loss of innocence when he knowingly let a pet chicken become dinner. Then with his back to the audience, he was dancing against a video backdrop of quick moving solarized scenes of China, people, traffic and streets. His vocabulary combined martial arts, ballet, and modern dance movements. And the music that wheezed in-and-out like a harmonica, eventually stopped. With his back to the audience, Wang was bent over from the waist, and both of his arms were spread out backwards like wings. Then Blackout.

|

|

Sudarshan Belsare |

|

Peter Chin |

|

Wen Wei |

|