|

| Caetano Veloso |

|

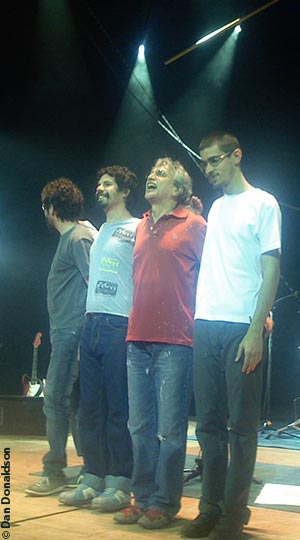

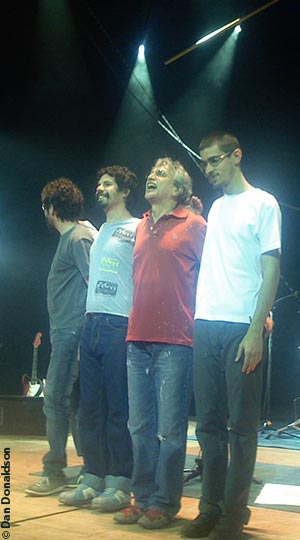

| November 11, 2007 • Massey Hall • Toronto |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Report and photos by Dan Donaldson |

Can it be that Caetano Veloso has never played Toronto before? After skipping Toronto in favour of Montreal's Jazz Festival during his Livro tour, and a cancelled date a couple of years ago, it was high time.

On a sparse stage, ranked with lights, strung with simple cords and rods that evoked a minimalist Carnaval staged by Calder, a small drum kit, a few mikes, a simple single keyboard, and guitar stands. Onto this, not the samba orchestra of the Livro tour, not the string sections of past performances, the massed percussion of the samba, but a rock trio backing up Brazil's living legend.

|

| Veloso is 64 years old. His career goes back more than four decades. He has 40 albums, almost all of which remain in print. He's played to adoring audiences on every continent except Antarctica, and he electrified a whole new audience with a chillingly beautiful performance that popped up in the middle of the great Spanish director Almodovar's film Habla Con Ella (Speak to Her). Hipsters know him through his leading role in the Tropicalia movement of the late sixties, lately anthologized in a have-to-have Pitchfork-ready collection. World Music aficionados (or dilettantes, depending on your point of view) know him because of his appearances on David Byrne's O Samba collection of fifteen years ago, which itself anthologized music already a decade old. Brazilians here and everywhere know him from his position as perpetual god of Brazilian music on TV and in countless duets and collaborations. Brazilians in Salvador, Caetano's original home town know him from his appearances in Carnaval, on the Trio Electricos, huge moving stages that move through the streets, party goers trailing, and from the huge string of Carnaval standards that he has written. Old Bossa Nova fans will have come across him, if they didn't know him before, as the producer of a beautiful CD released in 2000 by Joao Gilberto, the only living individual who could be said to be more important in Brazilian music than Caetano himself.

This, Caetano, is the problem when you put things off. With 40 years of waiting, what can you possibly bring us that would match this level of expectation? Those hoping for a Veloso nostalgic for himself were not going to get what they expected. What Veloso had in mind was a rock show.

|

|

Caetano Veloso |

|

Kicking in, the three backing members — Marcelo Callado on drums, Ricardo Dias Gomes on bass and Pedro Sá on guitar — were tight and effective, but overwhelmed Caetano in the mix. It took two or three songs until the soundman got it right, with “Nine Out of Ten”, a 1972 tune, written and sung in English: "I walk down Portobello Road to the sound of Reggae/I'm alive/the age of gold, yes the age of gold/the age of gold/the age of music is past." No doubt a bit of English set a number in the audience at ease. But the accessibility of the English lyric also underlined a theme that carries through Veloso's new album, and all through the show: the poignancy of time past, of age and anger, the rage against the dying of the light. Repeated, repeated: I'm alive.

Undeniably, this song is Caetano, just as much as any other, but not the Caetano that most think of first. Veloso has sometimes seemed a bit too ready to be complacent, to bask as one basks on a beach in the perpetual sun of Bahia, and that is how he is often presented, particularly to North American audiences who might find the linguistic complexity and astonishing poetry of Veloso's lyrics inaccessible. But if “Nine Out of Ten” wasn't that, the next song was, “Um Tom”, from one of the albums best received here, 1997's Livro. This, one of the sweetest of Veloso's songs, is built around a repeated figure, like the ticking of a clock, that still evokes the samba of the streets and beaches of Bahia. With a simple acoustic figure of hovering, bossa chords that never quite resolve, the song depends on the purity and sweetness of the voice to carry it off. This Veloso did — it was perhaps here that the audience began to understand how Veloso was going to connect the parts of his past, with the angelic voice that even now does not fail him. “Um Tom” — 'a tone' in Portuguese, but also a name, Tom, Tom Jobim — was dedicated to Jacques Morelenbaum, the great collaborator with Jobim, bossa nova's ultimate composer and always a counterpoint and complement to Veloso's own output.

That sweetness, at least that melodic sweetness continued with “O Homen Velho” (The Old Man), whose Portuguese lyrics both hid and shielded the English speakers in the audience from its bitter sweetness, while Veloso's voice, slightly darker, lower than in “Um Tom” sang: "Ele jà tem a alma saturada de poesia, soul e rock'n'roll/As coisas migram e ele serve de farol" (His soul is already saturated with poetry, soul and rock'n'roll/he acts as the lighthouse as things move on), and later: "A brisa leve traz o olor fulgaz/Do sexo das meninas" (The breeze carries back to him the sweet smell/of the young women’s sex). Somewhere in this poignancy, there's something that verges on creepy, but not in the delivery of Caetano. Forever the ambiguous androgyne, forever the Dionysus, someone who has forever taken the underlying sexuality of the singer and the song as part of the package, sometimes cynically, when considering the mythic 'tropical' allure of Brazil, sometimes as an ode, now as a eulogy. Veloso seemed to be resigned to what happens, but also unleashing an anger — an anger that could not have been clearer in the next song, "Homen".

“Homen”, translated, would have either angered, irritated or delighted, but not left many indifferent. About as far from a samba tune as he'll ever get, and rock of a different sort than the Tropicalia era, almost a chant, “Homen” (Man) asserts attitudes about women that include dismissals of intuition, fidelity and women's wisdom, a kind of gratitude at being spared lactation, menstruation and childbirth. The song is spared from irretrievable misogyny — although really, what is there to be jealous of in menstruation — by its chorus, which is a disgruntled acknowledgment that it might all be worth it for the longevity and, in particular the multiple orgasms. The confidence with which Veloso delivers the lyric, the sharp, clever wit and the preparedness to fully inhabit a persona make Veloso akin to the musician he is most often compared with here, the "Brazilian Dylan", but here it seemed more like Bowie, the nasty, snapping lyrics of the Diamond Dogs period, the sex infused bitchiness and erotic confidence. Did I mention that Veloso is 64?

|

Up-tempo, closest to a rocker in the North American sense, Veloso bounced on his toes, hammered on the guitar, and did what was required to build the excitement in stodgy Massey Hall. This continued with "Odeio", another tune off the album. In the chorus, he had the audience singing along with the simple refrain: "Odeio você, Odeio você, Odeio você, Odeio". It wasn't until after the song, returning to the mike and talking, in beautiful, Brazilian inflected-English, that he explained that the chorus means "I hate you, I hate you, I hate you...” something he clearly enjoyed, remarking that expressing hate was, in its own way, one of the purest expressions of love there could be, given that only those who we love or have loved can elicit it.

Odeio moved to “Amor Mais do Discreto”, a lyric that describes the tearing away of the sense of difference between ages, the negotiation between age and youth, the possibilities of mutual exchange, before the inevitable departure of youth, leaving the lover, like the old man, the lighthouse to that which moves on. All of this could be very maudlin and self-serving. But in lyric, music and delivery, Caetano has a hardness, a reality and a lack of illusion to him, something that one might not have said of someone who has spent a good deal of his life weaving playfully the threads of the myth of Brazil and the tropics, even if only to pick them apart again like Penelope, waiting for the return of Odysseus. It seems that the contemplation of age, the gaining of retrospective, the fact of age is what Veloso has been waiting for.

|

|

|

|

Caetano has reputedly recently gone through a messy divorce, and the temptation exists to interpret his lyrics, the tour, the new rock style, the band — which is composed of people half his age, friends of his son, Moreno, who also produced the latest record — in this light. Up to this point in the show, that might have seemed the case. But "Odeio" seemed to mark a shift in the show as well, almost something he had to get off his chest. Perhaps it was playing in a city he's never played before, but Veloso and the band seemed to be able to move comfortably between the material of Cê and older material that one associates with other periods in his career. Indeed, after “Amor Mais do Discreto”, the band left the stage, and Caetano sat, cross-legged with his acoustic guitar and played first “Coraçao Vagabundo”, then “Cucurucucu”, (the song from the Almodovar movie), and then, gloriously, “Sampa”, his hymn to Sao Paolo.

The band returned for a mix of tunes from Cé and older hits, at a couple of points letting loose for solos by Pedro Sá, whose gift is to keep the interpretations, the melodic lines vital, overlaying a strong rock sensibility on the samba underlying so much of Veloso's output. Every member of the band was born after Veloso's first hits, and must have had parents with his records in their collections. The North American perspective which can never really believe that people they've hardly heard of can be genuine stars back home wouldn't necessarily reveal the juxtaposition happening on the stage. That the band made so much of the music, never letting it collapse into a tribute or reverence is a huge credit to them, and to Veloso's courage in choosing them as his tour mates.

In the mix was a version of “Musa Híbrida”, a song on Cê that hearkens back to the music Veloso produced in the eighties and nineties, particularly with Arto Lindsay producing him. Whether it could stand up to the only major sing-along of the evening (a standard feature in Brazilian concerts), “Desde Que O Samba é Samba” is a question, but I felt it came off as a second best to the album version, and the only time in the show I was slightly bored. “Desde Que O Samba” swept that away, with Veloso taking it down to a minimal form, almost Bossa Nova as he's recorded it in the past, but with Sá working over the top of it to keep it alive and consistent with the tone of the rest of the music.

“London, London” managed to transcend its tendency to goofiness — it's one of the first songs Veloso wrote in English, back when he and Gilberto Gil were exiled in London in the late 60's and early 70's, and its lyrics have always seemed a little bit of a struggle, however charming, with the clumsy sounds of his new language, combined with a collision of what seemed random snippets of hippie-isms. But in the hands of its creator looking back, the song was transformed into a lyric of isolation and loss that echoed back through the concerns of the rest of the show, the specter of age that Veloso is clearly examining these days. The song has always had a lovely melody, vaguely reminiscent of the Beatles, the Velvets and Nick Drake, if a bit saccharine. Not this version.

“Fora de Ordem from Circulado” (1992), then “O Héroi”, then “Rocks”, both from the recent album, the former a spoken word piece over music reminiscent of “O Navio Negreiro” or “Haiti” in its tone, and whose lyric concerns are a kind of dystopian Tropicalismo, despairing of the world and ironic about the speaker's own role — "Eu sou Héroi/Só deus e eu sabemos como dói" "I'm a Hero/only god and I know how it is.” The excursion into spoken Portuguese was a reminder that in Brazil, Veloso is as much a poet, in much the way Leonard Cohen is taken seriously for his words more than his music, even though unlike Cohen, Veloso's poetry is entirely within his musical output.

The main part of the show over, and the inevitable encore; Veloso returned with the band to launch into "You Don't Know Me", a lyric asserting isolation, full of nostalgia, but holding out the possibility of a connection between people, again going back to the Transa album. Astonishingly, this moved into “Leaozinho”, a song so sweet, so almost innocent, so much a part of the Orphic image of Caetano, the curly headed quasi-hippy. This is a song that David Byrne introduced many North Americans to Caetano with when he anthologized it on the original O Samba record. I always regretted that this was included, not because it was a lesser song, but because it hid the parts of Veloso that seemed more fascinating: the synthesist, the collagist, the analyst of culture; “Leaozinho” was too much the face-value insipidity that Veloso was fascinated by, grist for a mill of transformation of sound and culture. In the concert, "Leaozinho" seemed a view into a golden age, the golden age of music that "Nine Out of Ten" asserts is over.

Caetano's voice has always been the most extraordinary instrument he composes for. That today, on stage without the protection of retakes, Veloso can take it through the indescribable sweetness, directness and make it not merely a bittersweet reminder of time passing as Billie Holiday's became, nor a caricature of limited expression like Dylan's, but a fountain of joy — even if the waters are acidic — is the source of the beauty and attractiveness of Caetano. In “Odeio” — which Veloso reprised in closing the show — the lyrics go:

Veio um garoto de Arraial do Cabo

Belo com um serafim

Forte e feliz feito um Deus, feito um diabo

Veio dizendo que sim

Só eu, velho, sou feio e ninguém

Odeio você...

[I saw a young man from Arraial do Cabo

Beautiful as an angel

Strong and joyous, made a God, made a demon

I saw him saying, yes,

Only I, old, am ugly and unimportant

I hate you...]

The beach in Brazil is cruel, but not in the way that the harsh Atlantic of Brazil's Portuguese forbears is. The danger and the terror lies not in being washed away, but being washed up. Caetano may write these lyrics, and he may no longer present himself as the eternally young god…

But then he takes a breath, and begins to sing...

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Dan Donaldson is a programmer and web guy who documents Toronto's Afro/Latin/Brazilian music on video. |

|

|