|

A thoughtful tone was set as Sundar & The Avataar Collective began with a repeating 4-note bass/tabla/voice unison that carefully arced into an Arabic-sounding, sinuous motif. Then John Kameel Farrah's skittering piano and Felicity Williams' exacting voice work swelled together to usher in an extended tabla conversation from Ravi Naimpally. Sundar's angular soprano solo grew investigative. Felicity sang in tricky intervals, and the piano vamped in sync. Soprano sax and voice took the tune out.

"Anger" was interesting because of its slow burn. There were no emotional flare-ups; instead, there was a building mood of voice chant, piano tinkles and shivering percussion. An agitated soprano/piano line next contrasted with the slow 'hang' of voice. Release came in the form of a soprano/voice duet of intricate interval stepping. A solo from Sundar and a solo from Felicity Williams becalmed the room. Very nice.

Soprano/voice match-ups were central to Sundar's jazz compositions. There was a Hindi intoning to these match-ups, a lonely sound that explored life's cycles of tension ("Twilight"), and release, as in "Tranquility", where voice and soprano together sang a slow aching tune vaguely reminiscent of Joe Zawinul's "In A Silent Way". It was a quiet benediction, a concluding peaceful moment.

Sundar's music is clearly a spiritual search for unity amidst the variety of forces that flow through life. Technically, it's an intelligent mix of the scales and tabla beats of Hindu music with the harmonies and rhythms of jazz. Like Hilario Duran, Sundar plays from his roots, but extends his search into the multicultural mix that many of us call jazz.

TASA was a crowd favorite because the six members played a tasteful, nuanced and sensitive music. Their set was a prime example of voice and drum music taken to a creative and personalized musical level.

When Samidha Joglekar sang in Hindi in a rising and falling voice, and Ravi Naimpally played descending bass lines and conversed with others on his tablas, the music took on a suspended, meditative quality.

But against — and playing with this soundscape — electric guitarist John Gzowski carefully squeezed out textured lines and spoke in fleeting R&B and blues drones. Especially in tunes like "Moonshine", he brought the vocal cry of the blues to the group's holistic sound.

Of course, John Kay's soprano and bansouri (Hindu bamboo flute played horizontally) added to and interrogated the flow of music which electric bassist Chris Gartner and drummer Alan Hetherington gently led on and simultaneously followed. There was an almost courtly pace to the music.

The beauty of inner worlds was depicted by TASA with finesse and delicate feeling. We clapped in head-nodding appreciation.

Then, the power bass — and funk! — of Brainfudge.

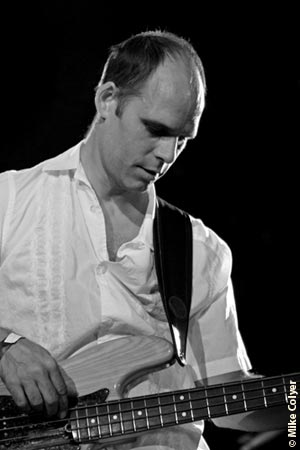

We're back in North America where the boot-stomping blues is alive in leader Chris Bottomley's electric bass, as he kept dropping low notes and letting them reverberate.

The first tune was a deep and brassy, call-and-response R&B riff — that hit hard. Richard Underhill came out flying on alto and developed his solo into a hard blowing, stabbing, and speechifying blues. Then a brisk drum interlude led into James Gray's final held chords that gently faded into the air.

"Random Splatter Effects" was launched by a singing bass and trombonist Steve Donald tonguing away in a kind of blues rush. All of it was urged on by the electric piano's colourful, sprinkled chords. Meanwhile, soloist Perry White got funky and really dug in on tenor, telling it like it is (and maybe what it ought to be).

There wasn't a lot to say, 'cuz "Brainfudge" really flushed things out!

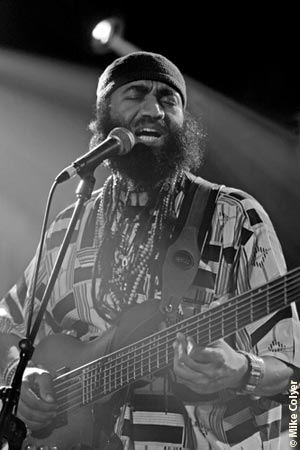

Headed by Sudanese-born multi-instrumentalist and vocalist Waleed Abdulhamid, Waleed Kush performed a ceremonial music that accompanies ritual and dance.

Accordingly, these 7 musicians shaped long, rump-rolling African vamps for everyone to play on and, in general, projected an 'Arabic/African' sound.

Within this sound-and-rhythm continuum, solo violinist Lawrence Dickinson frequently scribbled away in vigorous bowed sounds and always aimed for a state of rhapsody.

In "Mi-shima", the tune's smooth surface was animated by guitarist Abdulhamid's rhythmical/spoken singing style. His voice suggested there was a human journey occurring through time and space, and he was the observer.

The last and lengthy section of the set featured two African dancers — one male and one female — who leapt, crouched, spun, mirrored each other, and struck energetic, fast-moving geometrical poses as they moved athletically over the audience floor . The blurred and fast hands of the djembe player spurred on their dance from the stage.

In a strong musical and cultural statement, Jason Wilson put himself and his group, Jason Wilson & Tabarruk, forward as a reggae jazz group, or perhaps a jazz reggae group?

Along with reggae, Wilson easily mixed together folk elements of his Scots heritage as well as jazz and world music. The jazz feel was particularly strong and mostly came from Wilson on piano and tenor player Sugar Prince. Compared with the at-times-muddy sounding drum-centred groups, Wilson's group was clear and effective.

In their first tune, the reggae beat was echoed in Dave West's chunky guitar wails. Meanwhile, Sugar Prince's clear tenor cries kept us Trane-ing in on the inner music.

"Can't Root Up This Tree ... No Matter How Much You Try" Wilson then sang. Sugar Prince's tenor was soulful and fluent, like 'Mr.T'.

"Soul Bird, You Got Away From Me" — with its "Lady Madonna" riff — was all about personal liberation in dance and song and you heard the unison guitar/voice of West disappear into upper fret squeals that segued into the concluding and heart-rending, "It's The Same Old Song, Since You've Been Gone" ...

|