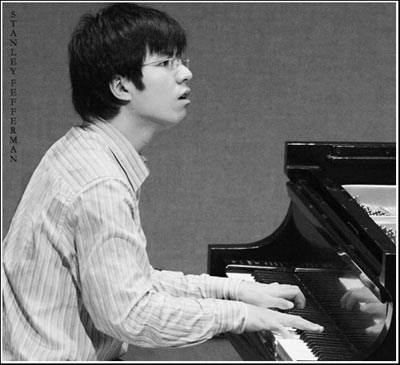

| Speaking about his sense of lyrical lightness Xiang Zou says that he hears the music that way and his hands are trained to follow. The energy of the music rises in his body, “and I try to fill the room with it.”

He can also bring thunder and lightning down onto the keyboard as he does before the closing fugue of the “Passacaglia”. The astonishing thing is that while his attack on the approach to the fugue embodies the power and velocity of a hawk stooping to strike its prey, Xiang Zou lands on the opening notes of the fugue like a butterfly.

Following the intermission, we were offered Schubert’s last piano sonata, the B flat major, D.960. This has been aptly described as ‘the’ example of supreme eloquence in the 19th century piano sonata repertoire, containing one of the great slow movements of all time.

From the opening trill low in the bass, follow waves of harmonic moments magical in their power to concentrate one’s attention. Not the least part of this power derives from Xiang Zou’s daring use of silences, achieved through fine pedal control and a uniquely spacious auditory sense. These silent intervals allow the sculptural qualities of the music to come through, as Schubert felt it, as if without interpretation. It is these silences and the spiritual understanding they enhalo that are the signature of Xiang Zou.

Though he stands on the threshold of his career, with a debut recital at Carnegie Hall two weeks away, Xiang Zou’s recent recording of the Schubert Piano Sonata in B flat Major will entitle him space beside Vladimir Horowitz and Stephen Kovacevich on the list of authoritative performers of Schubert’s piano music.

|