|

|

| Perú Negro

February 25, 2005 • Roy Thomson Hall • Toronto

|

|

|

| Report by Joyce Corbett |

| On this snowy February night in Toronto, with a performance that was polished, sophisticated, visually stunning and rythmically compelling, Perú Negro showed the audience that Afro-Peruvian culture has survived and lives on. Afro-Peruvian music and dance is still relatively unknown outside of Peru. The black population of Peru is small, representing no more than 5 to 10% of the total. Back in the days of slavery this proportion was much higher, at times, blacks even outnumbered the colonists.

Afro-Cuban music, Brazilian samba and bossa nova have had enormous impact on both sides of the Atlantic. And of course there’s the phenomenom of American jazz and blues. Black slavery was part of the history of colonization throughout the Caribbean and the Americas. So why is the legacy of African culture in Peru so little-known? Is it only because they constitute such a small minority today?

|

|

|

In Cuba, as in Haiti, most of the slave population came from Nigeria and neighbouring countries. The slaves of Peru came from a much wider African diaspora making it difficult to maintain traditions. Apparently, this was not an accident but a strategy to prevent insurrection. Some Peruvian slaves, especially those who served as domestics did not come directly from Africa but were “imported” from Spain. Some were even born in Spain. Add to this the usual suppression of African culture by the church and European colonists and it is not surprising that there remains no African language in the songs of Perú Negro. What is surprising is that Perú Negro exists.

Ethnomusicologists first started investigating Afro-Peruvian traditions in the 1940s. At that time, these traditions were very much in danger of being lost forever. Through the 50s, 60s and 70s, individual devotees, musicians, black pride movements, and for a while, government support, helped to recover and strengthen this musical heritage. Music and dance that had survived in the kitchens and the small coastal villages of Peru spread to Lima and on out to the world.

|

|

| Perú Negro was founded in 1969 by the late Ronaldo Campos de la Colina to preserve and develop Afro-Peruvian music and dance. In the seventies the group received funding from the government for its role as cultural ambassador to the world. The group is now led by his son, Ronaldo Junior. The seven musicians, two vocalists and ten dancers are currently touring North America.

Their music is a unique blend of African rhythms with Spanish guitar and flamenco influences. I did not hear anything I recognized as an element of the indigenous Quecha and Ayamara people’s musical traditions in Perú Negro’s Roy Thomson Hall performance, although they are another flavour in the Afro-Peruvian musical mixture. I did hear some filigreed guitar work in circular patterns I connect with Africa.

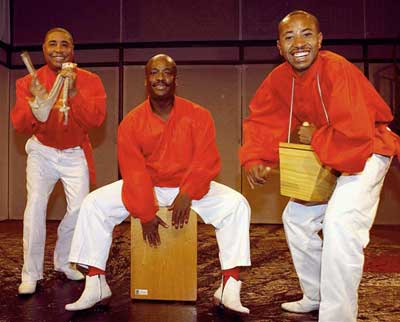

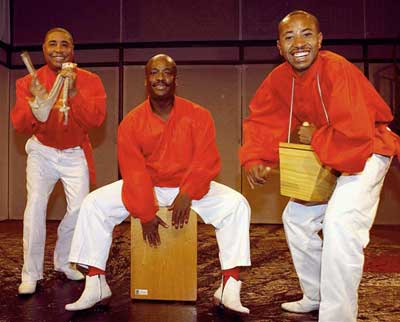

The rhythmic foundation is the cajón, a percussive box. The players usually sit astride it, hitting the front of the wooden box to produce syncopated rhythms. The cajón has evolved from the fruit crates the slaves used when African drums were banned. In recent decades it has been adopted by musicians from other countries and a version of it has become a staple in Flamenco, having been introduced by Paco de Lucia in the seventies after a visit to Peru.

|

| Other percussion intruments peculiar to Peru and born of necessity are the cajita and the quijada de burro. The cajita is another wooden box instrument, smaller than the cajón. Its origins? The collection box from church, played by flipping open the lid and clapping it closed with one hand while the other rubs along, or hits, the sides. The quijada de burro is a dried-out donkey jawbone. Struck with a stick, it continues to resonate by virtue of it’s tuning fork shape and the loosened teeth vibrate in sympathy. |

|

|

|

| So how does a Perú Negro performance look and sound?

Roy Thomson Hall, first piece, Afro dance.

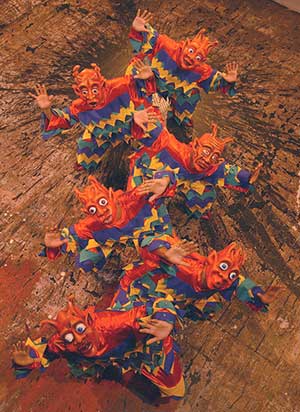

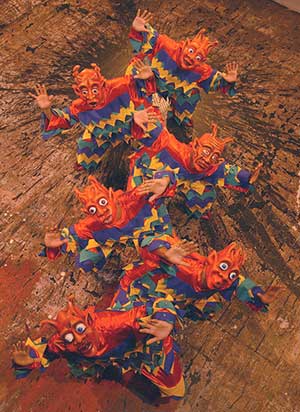

Total darkness—soft lights come up on the row of instruments at the back of the stage, waiting for the musicians who arrive to animate them. Stage light. The cajónes start the rhythm. Four men enter from stage right, four women from stage left. Their movements are stylized, syncopated. Sharp pelvic thrust. Stop. Statuesque. Shoulders lift. Stop. Shoulder roll left. Shoulder roll right. Stop. Short quick step forward. Stop. In this way, the lines of men and women, face to face, approach each other. New bits are added to each movement. Connections develop. The lines of women and men cross and recross. New, non-linear formations evolve. Men and women face each other, then away. Movements are syncopated but no longer disjointed. Arms push and pull. The oiled torsos of the men vibrate. Hands clap high in the air. Loose orange mid-calf pants allow unfettered movement. The cajónes, cowbell, congas, bongos and guitars are all playing and the drummer is producing a liquid sound from his djembe-like drum. All is frenzied but controlled. The women, dressed in printed African costumes with matching headwraps are now dancing around one man, while the three other men dance in a line to one side. The music quiets, the dancers break, and run lightly off stage.

|

|

|

I see this piece now as a metaphor for Afro-Peruvian culture. Fragments are recovered, bits and pieces are gathered and reconnected. The music and dance start to flow again, imbued with new life. They open to the world outside receiving and exerting influence while carrying on tradition. There is excitement, enthusiasm and much celebration. The jubilation of a harvest dance.

Ronaldo Campos de la Colina, the founder of Perú Negro, would be proud of this evening’s performance — mission accomplished.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|