| Tchaikovsky’s Francesca da Rimini, Symphonic Fantasy after Dante, Op.32 (1876)

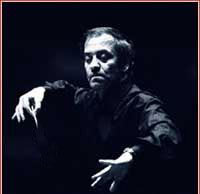

A whirlwind blowing through the gloom of Inferno where Dante meets the adulterous lovers Paulo and Francesca is the musical subject of the opening of Tchaikovsky’s Francesca da Rimini. Kirov’s big brass and percussion sections emit a tumult, deep, richly modulated and perfect in timing that alternates with sad, keening of winds and strings until Gergiev calls the orchestra to rest, quivers his left hand, flicks his right, calling out the solo clarinet, soft and eerie, followed by a succession of flutes, oboes and strings who tell, in the heartbreakingly beautiful melody of the andante cantabile, the lovers’ sorrowful tale. Their recitation is lyrical and lovely, with fluty birds and breezes blowing over meadows of grain. The orchestral sound is smooth, well oiled, silky as a lover’s skin. Then, as if he is calling it out of himself, Gergiev summons the hellish winds into which the couple recedes and are obliterated by the furious conclusion.

Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No.1 in D-flat Major, Op.10 (1911-12)

Daria Rabotkina, 24, recently accepted into the June, 2005 Van Cliburn Piano Competition in Texas, is the soloist for this work that the 20 year old Prokofiev composed and performed as his graduation piece from the St. Petersburg Conservatory.

Orchestra and piano start in gorgeous unison, Rabotkina’s tones, bell-like, percussive, riding over wave after orchestral wave, like foam racing at different paces so sprightly and joyous, it makes you want to laugh. The work is astonishingly playful with passages in the andante assai where the left hand plunks chords like a grandfather clock while the right hand plinks the highest crystalline notes and she builds slowly out of that into a unified solo of rolling and crashing waves of sound. The allegro scherzando emerges lyrical, softly flowing, Rabotkina’s touch both gentle and razor sharp, while from the Orchestra, Gergiev draws an infinite gradation of tones. Rabotkina’s closing cadenza is spellbinding.

Rimsky-Korsakov’s Capriccio espaniole, Op. 34 (1887)

This piece, like Tchaikovsky’s, was written in the composer’s 36th year. The opening Alborada dances on silvery winds in chorus and solo. Then follows a slower variazioni introduced by mournful horns, lyrical strings and an oboe solo floating dreamily in a gossamer mood, alive, trembling, and full-bodied. The familiar theme of the final fandango is brought in with a bango of drums and castanets. It is a lot of fun, swelling with string harmonies and piercing wind solos towards a celebratory ending with the 6 percussionists keeping a sharp eye on the maestro for their cue to go “BAM”.

Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition — 1874 (orchestrated by Maurice Ravel-1922).

Composed originally as a piano suite to honour a memorial exhibit of the artwork of Mussorgsky’s late friend, the painter V.A. Hartmann, this piece remained unpublished until five years after Mussorgsky’s own death in 1881. Orchestrated by many musicians, including Stokowski and Ashkenazi, Ravel’s retains its première place in the repertoire.

The suite aggrandizes the content of 10 of Hartmann’s pictures. The opening self-portrait of the composer walking through the exhibition begins with a brass fanfare and develops a sense of darkness, tension and hesitation suggesting ” the composer’s indecision as to which picture should be viewed next”.

The second picture, Il vecchio castello (“The Old Castle”) focuses on a singing troubadour. His nostalgic melody, introduced by winds, strings, and the slow, gentle flowing of bassoons, is developed by the saxophone into the loveliest of themes, mysterious, deep, and flowing like winds round the turret and courtyards of the decaying castle, till the melody is brought to stillness in the depths of the bass clarinet. In the Tuileries sequence, where high notes of the wind instruments suggest a dispute among children playing, the orchestra seems to breath like a large animal. And, it happens, that the next picture is of a cart on enormous wheels drawn by a pair of oxen. The main theme is carried by the tuba followed by the full orchestra which builds the impression of the huge heartbeat of the oxen, moving in a slow dance towards a fadeout. Subsequent depictions are of chicks dancing in their shells, a dialogue between two Polish Jews, the noisy chatter of housewives at a market, a meditation on death, the wild drive of a witch flying on a wooden pestle, and finally, the Great Gate of Kiev.

Additional delights. The Governor-General attended. The musicians were extraordinarily well dressed and shod. They were seated on the stage, not on a makeshift platform, and the Maestro shared the floor with them, without podium, without rail, without formality, without any artificial barriers between him, his musicians, and his audience, and the music embraced us all. Bravo.

|